|

|

|

|

Hear what sixty years of banjo playing can do to a person. |

|

ď.

. . Thereíll be a great Hootenanny by and by Thereíll

be some folksong singiní in the sky They

will lay aside their harps When

that banjo pickiní starts

In

that great Hootenanny in the sky. . .Ē On

January 29, 2016, Billy followed the path through those gates to meet

his friends who had gone ahead. We figure heís still busy, walking his

2 miles a day, juggling whatever is at hand, still blowing folks away

with his picking prowess, and jotting notes for the Heavenly Press. If

thereís hitchhiking in Heaven, heíll be there. We

miss him like crazy. cw/gh |

|

Billy's site has been almost entirely preserved as it was before his passing. It remains in the first person. |

|

You can listen to all the music on this web site or download it free. To listen, left click on the underlined title, being sure your speakers are on. Then use the "back" button on your browser to return from the black screen to the page where you started. To download, left click on the underlined title (as just previously noted), then right click anywhere on the player. (You might want to pause the player). The options that pop up will vary with your browser but should let you "save," "download" etc. In each case use your "back" button to return to the origin page. You might wish to set up a target subdirectory for the files you are saving, or let them accumulate in your download directory and move them later. |

I was born on Dec. 21, 1978 RPM. I hated every minute of it until we moved to Woodstock, New York in 1945 at which time and place I discovered that the world had good stuff in it, too. It was there I had my first intro to folk music, (except for the folk songs I had been singing all my life and didnít know thatís what they were.) Many of the artists, writers and musicians, in Woodstock, sang folk stuff and played the guitar. There was a camaraderie among these folks that was new to me. Not only did they seem to like and understand each other, but they included me in that communal umbrella of feeling, even though I was new to them and just a fourteen year old kid. In Brooklyn I had been patronized, ignored, or abused by most of my so-called schoolmates. In Kingston High, where I now went to school, the same was true, but here in Woodstock there was this other group of people who accepted me. These were the Ďartistsí of the Woodstock art colony. They also had an intense love of the place they lived; the community of Woodstock and the Catskill Mountains. It gave me, for the first time in my life, an intense feeling of BELONGING to something bigger than myself.

(One of the biggest reasons I like living in Texas; itís the only place I ever saw where the inhabitants love to sit around the campfire half the night singing songs about their home state. Can you imagine this happening in New York? New Jersey? Of course not.)

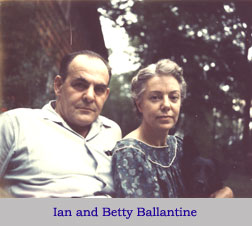

Betty Ballantine was the first person I

ever heard sing a song while accompanying herself on a guitar. There was square

dancing at the Irvington Inn every Saturday night attended mostly by the artist

community. At the end of the dance, one night, Betty invited everyone to her

house to continue the party. She made sure that I, the shy teenager, knew I was

invited. The first song she did was UNFORTUNATE MISS BAILEY, about a young maiden

who hung herself in shame after allowing herself to be seduced by a Captain

Smith. Everybody at the party knew and loved the song and lustily joined in the

chorus;

Betty Ballantine was the first person I

ever heard sing a song while accompanying herself on a guitar. There was square

dancing at the Irvington Inn every Saturday night attended mostly by the artist

community. At the end of the dance, one night, Betty invited everyone to her

house to continue the party. She made sure that I, the shy teenager, knew I was

invited. The first song she did was UNFORTUNATE MISS BAILEY, about a young maiden

who hung herself in shame after allowing herself to be seduced by a Captain

Smith. Everybody at the party knew and loved the song and lustily joined in the

chorus;

"O, Miss Bailey

Unfortunate Miss Bailey..."

But my real awakening to folk happened

in Washington Square one Sunday afternoon in October of 1947. There I saw all

sorts of people, kids like myself and adults, all singing the songs we came to

know as folk songs. It was a weekly gathering which moved indoors to Gabe Katzís

place when it got cold. This, for me, was the beginning of the so-called Urban

Folk Revival (UFR) and second introduction to the intense joy of group singing. I

started playing five string banjo at that time, giving up a promising career in

the world of business, to devote myself to music and women. For the next ten

years I learned to play the banjo and guitar.

But my real awakening to folk happened

in Washington Square one Sunday afternoon in October of 1947. There I saw all

sorts of people, kids like myself and adults, all singing the songs we came to

know as folk songs. It was a weekly gathering which moved indoors to Gabe Katzís

place when it got cold. This, for me, was the beginning of the so-called Urban

Folk Revival (UFR) and second introduction to the intense joy of group singing. I

started playing five string banjo at that time, giving up a promising career in

the world of business, to devote myself to music and women. For the next ten

years I learned to play the banjo and guitar.

From the age of seventeen to

twenty one I lived in a cold water flat on East Fifth and Avenue D in the lower

East side of New York. The rent was seventeen dollars a month. Besides the

people of the folk community I knew many young poets, painters, Anarchists,

Socialists, and Communists. I mention only a few of them who stayed

with me. Harold James Nicholas, a painter whom I admired. Trying to sublet

my apartment, I met a young woman, Ruth, who came to see the place. When I asked

her what she did for a living, she hesitated, blushed, and then said, quite

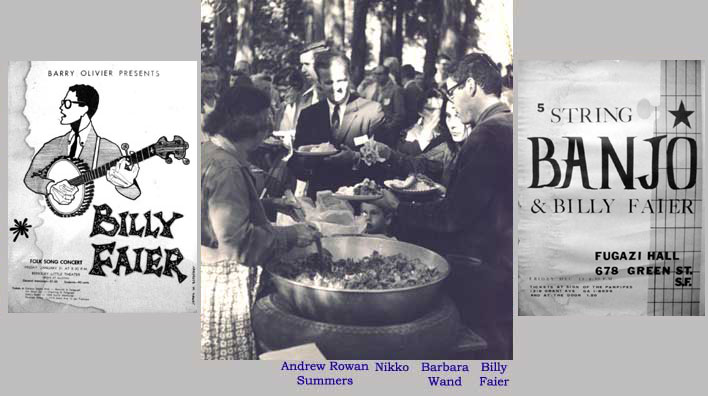

defiantly, "I'm a Communist". My friend Nikko's ears perked up at this

and before long the two were an item, big time. In

no time his paintings changed from what I can't remember, to heavy socialist art

a la Diego Rivera. It was a fascinating process to see.

Bob Kaufman was one of the early Beat Poets. His major piece was THE

ABOMINIST MANIFESTO, published by City Lights in San Francisco. He stayed for a

while. Bill Kehoe was an artist who spent most of his time drawing arrows,

cubes, geometric forms of all sorts. The conversations between him and

Nikko about art and life were fascinating and quite unintelligible to me. Eric

Weinberg stayed for a while. He was a carny and loved to do magic tricks.

Last I saw him was when I interviewed him on a public affairs program I ran on

WBAI in New York. He had just won a Peace Prize for his work in India.

John Kelly was a buddhist. He wrote and spoke Sanskrit. His

social graces were nil. I first knew him in my earliest Woodstock days.

Every few years he would inherit a few hundred thousand dollars from a departing

relative, which he would promptly give away. Later, when I was living in New

York, Ricky Sanchez asked me to put him up which I was glad to do. Most of

the time he did nothing but sit and meditate. I would leave for work in

the morning, when I worked as an orderly in the operating rooms at Beth David

Hospital, leaving John sitting on the living room floor with a cigarette burning

in his hand. He always held his cigarette straight up as he meditated. He would

still be in the exact same position when I returned hours later, the cigarette

out but the entire ash still in place, pointing up to the ceiling.

Rick Sanchez was a wild eyed painter who lived in Woodstock when I was a

fourteen year old, new to town. He later lived with Selma Benjamin who was one

of three women who frequently came to the Friday night folksings at Gabe

Katz's on East 10th Street, where the Washington Square folk crowd met when the

weather got too cold for outdoors. They were Anita Steckle, Selma Benjamin, and

Jeannie Neal. They were extremely hot and desirable to my virginal teenage

eyes. And they certainly livened up the folksings considerably. After a

few months they were followed by the drummers who changed the character of our

precious gatherings and most of the old time folkniks stopped coming.

I knew other musicians besides the folk players. Bob Casey, an old time Jazz

bassist, turned me on to playing at Columbus Circle for the tourist couples who

rode the horse carriages. I tried it one time. I was sitting on a bench on

the crowded circle playing my banjo very quietly. I was very shy then. A

black man started yelling at me for doing so, shouting "Why can't you let

us forget?" Apparently the negative stereotype of associating blacks with

banjos was still with him. This was the late forties. Pete Seeger was

pretty esoteric still, and Scruggs was not well known in New York.

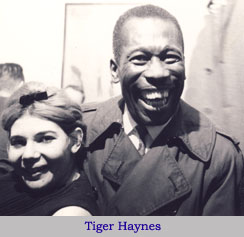

Milliard Thomas was usually around. He played

classical guitar and taught me a few things about it. Harry Belfonte was

cooking burgers at the SAGE, a small joint on Sheridan Square. But my favorite

non folk musician was Tiger Haynes. He had a group called the THREE

FLAMES. They had a steady gig at a club on Eighth Street in the Village.

Tiger had a style of guitar that was incredible. He was a master of

harmonics. He loved a good friend of mine, Elaine Lanciano. She and

I loved playing together and Tiger and I became good friends.

During that time I became acquainted with anarchy, poetry, Buddhism and marijuana. (But grass made me sick the first three times I tried it because I smoked too much, too soon. I was a cigarette smoker and smoked dope like it was tobacco. So, thinking, "Since it makes me sick, it must make everybody sick. All those dopers must be masochists. I am not a masochist," I gave it up for the next ten years. I had a lot to learn.)

In 1951 I was about to be drafted and sent to Korea to get killed so I decided I would not serve in the military under any conditions. I would refuse induction. Thinking I was going to spend the next ten years or so in prison, I made a Ďfinalí trip to Oregon with Mariel Patterson. When we arrived at her motherís house in Portland there was a telegram from Emmett Edwards (whom I had left in my apartment in New York) telling me I was expected at the draft board in New York the next morning for my army physical. I called the Portland draft board explaining my situation. They told me to sit tight while they had me transferred. Two months later I took the physical in Portland and I was 4F, no army, no jail. For those two months Mariel and I worked picking blackberries. It was there, in the blackberry fields, that I first heard a folk song in its natural setting--the forewoman of the picking crew singing, in a lusty raucous voice, TWENTY-ONE YEARS. It was a thrill.

I hitchhiked to San Francisco, looking forward with great anticipation to being in a new place where I could leave my past, my hang-ups, and problems behind, and just be who I "really am!" HAH!!

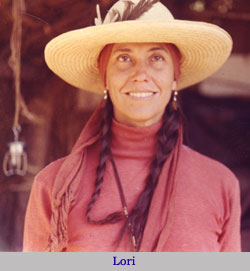

I met Barbara Dane, Rolf Cahn, Paul and Jo Mapes, Stan Wilson, Lori Blakeslee and many other folksingers from the Bay Area.

I married Lori and her two boys and we

went down to live in Mexico for a year. Then up to New Orleans where the heady

events of Rambliní Jack Elliottís

912 GREENS took place.

I married Lori and her two boys and we

went down to live in Mexico for a year. Then up to New Orleans where the heady

events of Rambliní Jack Elliottís

912 GREENS took place.

The dumbest thing I have ever done was to leave my first wife, Lori. She is nine years older than me and taught me valuable stuff I might never have learned without her. She played guitar and sang like an angel. I left her because, in my raw post-adolescent maturity, I thought I needed to be "free." And now, fifty-five years later I realize that I had more freedom then than I have ever had since. Live and learn!

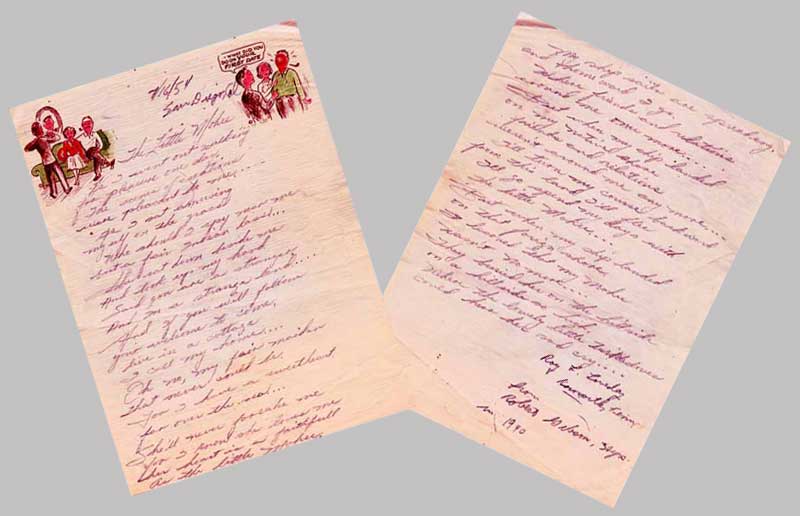

In 1954 a trip across the country with Woodie Guthrie, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, and Brew Moore, following the woman I loved, landed me in a cheap downtown hotel in San Diego. Playing my banjo in my room one evening attracted a young sailor, Roy Loveday, from Knoxville, Tennessee, from the next room. He came in and we swapped songs for a while. Then he came up with this gem.

A young girl, no more than seventeen, seemingly down and out, heard us and came over, wanting to be part of the party. When she saw I was really interested in Roy's songs, she went back to her room for some writing material and wrote down for me some of the songs he sang on her pink high school stationary.

In San Diego I got a job driving a Good Humor Ice Cream truck with a music box. My music box was a hopped up version of the Star-Spangled Banner. Being the new man, I got the worst route, the one where the poor folks lived. My fellow drivers suggested I steer clear of the "Pig farm", by which they meant the Black enclave in National City. It was Sunday morning I first pulled in there. There was a church with singing coming out of it. I sat in the back until the music was over, the only white face there.

When church broke I went out to my truck, hoping to sell some ice cream. I was completely ignored by the departing congregation until one little girl couldn't resist checking me out, I gave her an ice cream and she ran back to the group. That, of course, got all the kids wanting ice cream and soon they were all there, nickels and dimes in hand, trying to get some. I asked them if they knew any game songs and was amply rewarded when a bunch of girls did,

"Little Sally Walker settin' in a saucer,

Waitin' for the old man to come for the dollar.

Ride, Sally, ride. Put your hands on your hips,

Let your backbone slip. I

shake it to the East, I

shake it to the west, I

shake it to the very one that I love the best."

They did it with the little dance, the handclapping, and all. Somehow, it was practically verbatim with Lomax's version in FOLK SONG USA.

I had been in La Jolla for two years, trying to make sense of it all. Frank Hamilton came down with Adam, a bass player. We played music one night at my house and decided to form a folk trio. I went back to L. A. with them. We stayed at Adam's house in Norwalk, but only for a few days. Our trio did not work out, so Frank and I went to stay with Guy Carawan in Venice, California. That was the beginning of a year in L. A. I hung out with Herb Cohen, Frank, Odetta, Ramblin' Jack, Derroll Adams, Fred Gerlach, Victor Maymudes and many others.

Then my very first fully professional gig at the GATE OF HORN in Chicago. It was owned by Albert Grossman who was a complete drag to work for. The bartender was called Spaghetti.

The first time I walked into the place I was greeted with;

CUSTOMER: Hey Spaghetti, how come you are called Spaghetti?

SPAGHETTI: Because I like to eat spaghetti.

CUSTOMER: So why don't they call Al Grossman Cunt?

It was downhill from there on. A rough two weeks.

On to New York

where I lived with Dick Rosmini and his mother, Lucia Rosmini in the triangular

building at 40 Jane street in Greenwich Village. Bob Gibson was a regular there

and he and I got to be fairly tight. One day, driving uptown in his car, he

asked me, "Billy, how come you never

recorded?" I had no ready answer. Naturally I had fantasies of recording,

but never felt I was ready, whatever that means. I told Bob,

"No one ever asked me."

On to New York

where I lived with Dick Rosmini and his mother, Lucia Rosmini in the triangular

building at 40 Jane street in Greenwich Village. Bob Gibson was a regular there

and he and I got to be fairly tight. One day, driving uptown in his car, he

asked me, "Billy, how come you never

recorded?" I had no ready answer. Naturally I had fantasies of recording,

but never felt I was ready, whatever that means. I told Bob,

"No one ever asked me."

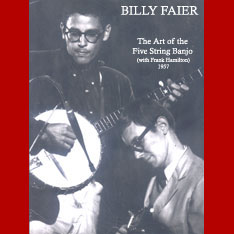

"Well, let's take a ride to Riverside and see Bill Grauer." I had my banjo. We drove to Riverside Records. On the way, we spoke of the possibility of me recording and Bob asked what I would call it if it happened. I had just become acquainted with Johan Sebastian Bachís ART OF THE FUGUE. I immediately answered, "The Art of the Five String Banjo. Do you think thatís too much?" Bob grinned and said, "No, Man! I think its cool."

I had very little faith in the possible outcome of this move. I know Bob meant well but I didnít think he had the clout at Riverside. But Bill Grauer and Orin Keepnews both greeted us as soon as we came in. I played for about ten minutes---I think I played SAILOR'S HORNPIPE. Half an hour later I had a contract and Bob and I walked out, pleased as punch.

I knew from the beginning that I wanted

Frank Hamilton to play guitar on my album. It was very hard refusing Dick

Rosmini, who wanted to do it in the worst way. He and Lucia had been very kind

to me, putting me up for months, but there were problems in my relationship with

Dick and I was afraid these problems would spill over into the music. Frank, on

the other hand, kept his feelings pretty much to himself. I had known him since

New Orleans when he arrived with Rambliní Jack and Guy Carawan. His guitar

playing was always rich, controlled, entirely appropriate, to the point, and

beautiful. And he was glad to do it.

I knew from the beginning that I wanted

Frank Hamilton to play guitar on my album. It was very hard refusing Dick

Rosmini, who wanted to do it in the worst way. He and Lucia had been very kind

to me, putting me up for months, but there were problems in my relationship with

Dick and I was afraid these problems would spill over into the music. Frank, on

the other hand, kept his feelings pretty much to himself. I had known him since

New Orleans when he arrived with Rambliní Jack and Guy Carawan. His guitar

playing was always rich, controlled, entirely appropriate, to the point, and

beautiful. And he was glad to do it.

The album would be produced by Kenneth

Goldstein who did all of Riverside's folklore series. I had many complaints about

the way he did it but I have long since gotten over it all. He got Pete Seeger

to do the back jacket notes, a great honor to me at the timeóand still.

I have replaced the original album cover with the photo of Frank Hamilton and I performing

at the l959 Newport Folk Festival.

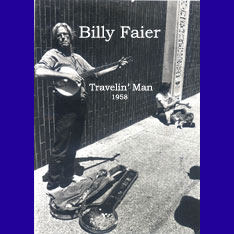

The album was recorded in 1957. A year later I recorded TRAVELIN' MAN. Mostly solo.

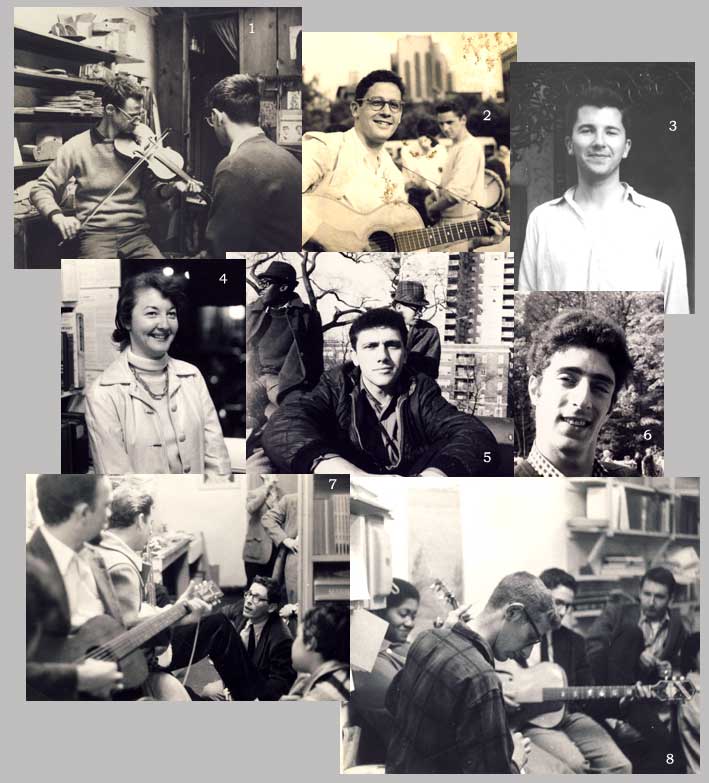

1. Fiddler is Allan Block,

sandlemaker. He

sold me my

first banjo and two lessons for

$20.

2. Me and Guy Carawan,

Washington Square.

3. Lee Haring, well known

folklorist and oldest friend.

4. Kennetha Stewart who did

most of the production work

for CARAVAN.

5. Roy Berkeley, friend and

fellow radical.

6. John Herald.

7. Anyone recognize the guitar

player? Guy Carawan, me, and Gina Glazer.

8. Odetta Felious, Dick

Weissman, me, and

Logan English

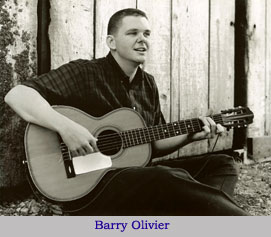

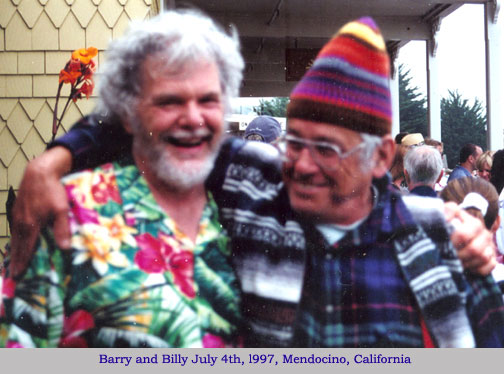

In July of 1957 I returned to

California to be with Barbara and our son. I met BARRY OLIVIER who was

the Bay Area's best promoter of folk music events. Unlike most music

promoters, Barry had integrity up the wazoo, was completely honest, and always

kept his word. In 1959 he produced the first Berkeley Folk Festival at the

University of California. I was not a star of the Festival but Barry, who loved

my music, went out of his way to help me shine. He put me on in concert at

the Berkeley Little Theater and at the North Gate Coffee House where he ran a

weekly folk music program.

In July of 1957 I returned to

California to be with Barbara and our son. I met BARRY OLIVIER who was

the Bay Area's best promoter of folk music events. Unlike most music

promoters, Barry had integrity up the wazoo, was completely honest, and always

kept his word. In 1959 he produced the first Berkeley Folk Festival at the

University of California. I was not a star of the Festival but Barry, who loved

my music, went out of his way to help me shine. He put me on in concert at

the Berkeley Little Theater and at the North Gate Coffee House where he ran a

weekly folk music program.

In 1957 and 58 I had a half hour radio program,THE STORY OF FOLK MUSIC on station KPFA, the very first listener sponsored station. Barry also had a show on that station.

In December of '57 I produced myself in concert, for the first and only time, at Fugazi Hall in San Francisco. The night after, Barry played a recording of that concert on his radio show. The pieces below are from the two concerts; Fugazi Hall, and the Berkeley Little Theater.

In the late fifties I took over CARAVAN, The

Magazine of Folk Music from Lee Shaw who ran it as a fun-filled fanzine. I tried

to make a more scholarly magazine out of it. I think I published the very

first discography of Hillbilly music with the help of Archie Green.

Kennetha Stewart did most of the production work of the six or seven issues I

put out. Lee Haring, Roger Abrams, Archie Green, and many

other writers and musicians helped me with their contributions of many

kinds. No one got paid except the printer, Peter Strauss, who

also helped me out whenever he could. At the end he waited a long time for

his money. When I finally went to pay him I apologized for making him wait so

long.

In the late fifties I took over CARAVAN, The

Magazine of Folk Music from Lee Shaw who ran it as a fun-filled fanzine. I tried

to make a more scholarly magazine out of it. I think I published the very

first discography of Hillbilly music with the help of Archie Green.

Kennetha Stewart did most of the production work of the six or seven issues I

put out. Lee Haring, Roger Abrams, Archie Green, and many

other writers and musicians helped me with their contributions of many

kinds. No one got paid except the printer, Peter Strauss, who

also helped me out whenever he could. At the end he waited a long time for

his money. When I finally went to pay him I apologized for making him wait so

long.

He laughed and said,

"At least you paid me. Riverside still owes me fifty-thousand bucks for the folk album covers."

In l958 my banjo and I became a nonessential frill in the Broadway production of THE UNSINKABLE MOLLY BROWN. Meredith Wilson wrote the music for the show. His father had played the five string banjo and he always wanted to get a five string into one of his shows to honor his father. It was a great job. I was only in one scene, the second, and was through by nine o'clock. But I was expected to appear in costume at curtain call, a real drag, after opening night. Here's how I worked that one out. The stage manager, the real boss of the show after opening night, was John Barrere. He was the son of the woman my ex-step father married two wives after my mother. Vasco was on his second wife after Mrs. Barrere. I asked the stage manager if I could be excused from curtain call.

"Absolutely not!", he said, "If you are going to be in theater you must be a professional about it. You have to have a dammed good reason to be excused from curtain call."

"I think I do, John."

"O yeah? What is it?"

"We have the same ex-step-father."

"VASCO PINI?", he shouted. I nodded.

"O, you poor kid. Go on."

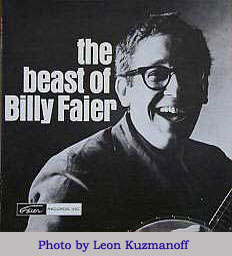

About this time I got married again. My wife

and I bought some land in Lake Hill, near Woodstock, and started building a

house. By '61 the marriage was over and she got an Alabama divorce on the way to

California. I got turned on to Rock and roll big time by the Beatles. It was

their album, RUBBER SOUL that did it. And the Civil Rights movement was

heating up. These two influences combined in me and I wrote about two dozen

songs about sex, drugs, love, and Civil Rights. Many of

them became THE BEAST OF BILLY FAIER.

John Sebastian plays guitar and harmonica on this

album. I met him years before when I was playing my guitar in Washington

Square. He was apprenticed to a guitar builder then and he talked me into

letting him rebuild my guitar under the supervision of his boss. I went

for it and when he brought the finished guitar back to me he played his harp

along with me as I was testing it out. He was a dynamite harp player

already. I asked him why he was learning to build guitars when really good

harmonica players were so rare and in demand in the recording studios. He said

he couldn't read music so he didn't think he could do it. I pointed out to him

that he had just played three tunes with me that he had never heard before

and didn't seem to have any trouble playing them. I urged him to try for

the sideman work that was going begging. About a year later he hailed me

on the street in Woodstock and announced that he had taken my advice and was

working almost full time playing the harp. And he told me how much he had

made in that year. It was four times my own income.

The BEAST came out in l964. I put all my advertising eggs into the SING OUT basket, a huge mistake, as it turned out. In the following issue publisher and editor, Irwin Silber wrote a long piece slamming me because of a single line in very small type on the back of the jacket, under the ordering coupon, NO ORDERS TAKEN FROM THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI. Swell-headed with the power of producing my own album, I was trying to be both au courant and humorous. I would never do it today. But SING OUT never reviewed the album. From my autobiography, written in 2006;

When I issued THE BEAST OF BILLY FAIER IN 1964, I made a symbolic gesture on the back of the jacket. In small print under the price information it said, NO ORDERS TAKEN FROM THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI. I never dreamed that any intelligent person would take it seriously. It was stupid of me, not well thought out. The idea of a personal boycott, however, came from the pages of Sing Out, the left wing folk song journal run by Irwin Silber. In issue after issue the idea of people making a personal stand in the cause of equality, freedom, and justice was manifest, both openly and implicitly. Silber wrote a scathing column about my stand.

After the opening polemics he says,

ĎPresumably Mr. Faier does not want to do business with white racists in Mississippi. Should a negro in Mississippi who might want to order one of Mr. Faierís records send along a photograph or an affidavit testifying to his skin color?í

Well Mr. Silber, your presumptions are wrong. I do not write for the already convinced audience, looking for their applause at how well I can put our mutually held convictions into song, as most of your topical songwriters seem to do. White racists are the ones who I would love to sell my records to in the hopes that the messages in my songs have an effect on them and their racism. Thatís why I wrote the songs, to change people.

Furthermore, you never would have asked the question about the Ďnegro in Mississippií if you didnít believe that all whites in Mississippi are racists.

You called it an ass-backwards approach and a cheap trick to cash in on a good cause. Gratuitous insults!!

You didnít like it because it didnít agree with your idea of how the Civil Rights Movement should be fought. I could go on analyzing your tripe. But the worst thing about it is that you didnít review the record. Had you done so, along with your criticism of my efforts, I would have had no complaints. And perhaps you would have changed your point of view about who I am. Finally, having accepted the ad, and then turning around and blasting it is really the cheapest trick of all. Money, money, money!!!

Website readers please forgive my digging up this old stuff. It has stuck in my craw the last forty some odd years.

I wrote about fifteen Rock and Roll songs in the sixties. None of them have ever been published or recorded, except for ROSE ANNE, on the BEAST. Go down to the first group, below.

I had a few Beatle songs in my repertoire. The only one I still do is:

| YOU WON'T SEE ME |

I get to use the GREEN CORN strum in it.

|

|

| I have a

tape of a performance at

Cafť Lena

in Saratoga Springs, New York. I did these Beatles songs:

|

||

|

FOR

NO ONE

|

||

|

NORWEGIAN

WOOD

|

||

|

I'VE

JUST SEEN A FACE

|

||

| A LITTLE HELP FROM MY FRIENDS |

|

|

I was going to do a CD of Beatle songs. I still might.

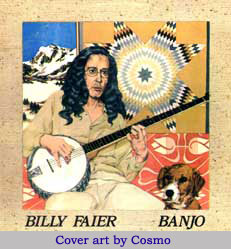

I think the best music I

have played on record is the album BANJO which I did for Takoma in 1973. That LP consisted of nine original

compositions, no folk stuff. I had just gotten turned on to John Fahey and

Takoma Records and I decided that I wanted to record for them. Cosmo

and I were planning a trip out West and we decided to give Takoma a try.

I think the best music I

have played on record is the album BANJO which I did for Takoma in 1973. That LP consisted of nine original

compositions, no folk stuff. I had just gotten turned on to John Fahey and

Takoma Records and I decided that I wanted to record for them. Cosmo

and I were planning a trip out West and we decided to give Takoma a try.

Gloria Anne Charles--Cosmo--is the most talented person I have ever known in my life. The three years I spent with her were the best I have ever known. She has absolutely magic hands with which she creates beautiful things which, to ordinary mortals, seem to be perfect. Her cooking, her sewing, her gardening, whatever she does with her hands are always a delight. I taught her to play guitar. In only a couple of months she was able to accompany me in most of my music perfectly. I have been blessed!

Cosmo and I decided I

would walk into Takoma cold--just like at Riverside.

Not that my "stuff" is that hard. But musicians who can sit down and play with someone they have never seen or heard before, and make the music ring true, are very rare. The act of hearing music is almost totally separate and distinct from the act of playing music. Hearing music involves focusing and appreciating. Playing music involves muscular action and different parts of the nervous system are involved.

After a couple of hours of dealing with all this I realized that I didn't want to record under these circumstances. So we agreed that I would handle the recording myself when I got back to Woodstock.

On the way back we

stopped to check out Santa Fe and ran into Jerry Faires, Jim Bowie, and THE

FAMILY LOTUS. We made a strong connection with them. They loved my music and

played it like their own. We decided to use them for the Takoma recording.

But, in the studio we weren't able to recapture what had excited us about each

other before. However Cosmo and I became good friends with Jerry and

Jim. Jim Bowie is high on my list of great banjo players. Here is a take

from the unused recording. Jim's banjo doing the high parts. Hugh is

on the cello.

On the way back we

stopped to check out Santa Fe and ran into Jerry Faires, Jim Bowie, and THE

FAMILY LOTUS. We made a strong connection with them. They loved my music and

played it like their own. We decided to use them for the Takoma recording.

But, in the studio we weren't able to recapture what had excited us about each

other before. However Cosmo and I became good friends with Jerry and

Jim. Jim Bowie is high on my list of great banjo players. Here is a take

from the unused recording. Jim's banjo doing the high parts. Hugh is

on the cello.

Back in Woodstock I got Alex Osina to record the Takoma Album. Alex was glad to do it for two hundred dollars, which was the amount Takoma allowed me. I had spent that on the studio in New Mexico so I had to pay Alex from my own pocket. We spent about two weeks recording nine tunes on his tubular Ampex. When we were about finished I spotted a tiny flutter of a whisper of sound against the places that were supposed to be silent. It was a defective tube and we had to do it all over again. It took us another week. By this time my chops were so good that the entire thing came out wonderfully.

Cosmo painted a portrait of me playing and included Pizza, my dog, for the album cover. And she sewed up an old quilt pattern for the back, both of which made it to the final cover. So, with all the outstanding crap and nonsense we went through, the final result was worth it.

I have two live performances on CD. (Live at the Cafe Lena) from the sixties and (Downstairs Concert 2007)

And I have recorded and performed with many other folk singers though my main act was always as a solo. I have traveled over the Western Hemisphere of the Earth with my banjo on all levels from professional concertizer to itinerant street musician. I live today in Marathon, Texas where I run my website, billyfaier.com, and play banjo and piano.

A few years ago I donated all my old reel to reel tapes and papers, letters etc. to the Southern Folklife Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chappell Hill. The request came through Bill Ferris, a well known folk and blues collector who is also donor to the collection. I was surprised and flattered by the request and I asked Bill,

"Why me? There are thousands of folksingers like me." Ferris laughed and said, "No Billy, there are only about five of you old timers who not only have been playing since the late forties, but who have also made a significant contribution to their art form." I could live with that and I made the donations.

Recently I have been having difficulties playing. After ten minutes, more or less, my hand gets numb, and I can't play. Carpel Tunnel Syndrome, it seems to be. It was obvious that if the usual therapy (a minor surgical procedure) were not effective, my professional career, such as it is, was over. If I could not record again I needed to gather up everything I had ever done. So I recently went to North Carolina and went through all those old tapes, mostly stuff I had done around my house, and, to my delight, found eighty good pieces instead of the dozen or so I had expected. Instrumentals and songs I forgot I had recorded were there. Even a couple of things I had no memory of at all. None ever commercially recorded. A real find.

Finding those eighty pieces of my old playing was incredible. But even more incredible is the fact that I had the Carpel Tunnel operation in San Francisco on July 7th, and now the operation seems to be a success. My playing is coming back quickly, better than it has been for the last four years. I had gone back to these old tapes expecting to find maybe six or seven pieces I could use. I wanted to use them to sell on CD's because if the operation was not a real success, my playing career was over. So I am blessed with both; my playing and these old pieces I had forgotten about.

I have roughly divided these pieces into groupings for the purposes of this website.

Previously unpublished performances

Concert at Berkeley Little Theater, Berkeley, California, May 2, 1958.

To those of you who have

purchased my CDs, my heartfelt thanks. But now I had decided to make all my

music free and available to everyone. You can listen to it right here or

download it by clicking on the album names above or the album images below. If you still wish to purchase the

albums in CD form, they are also still available, as are tablatures of

many of my tunes. Your donations are welcome and should be sent to (his

grandson) at:

Christopher H. Wand

P.O. Box 1398

Sausalito, CA 94966

You can email Chris at christopher.h.wand@gmail.com or call (415) 531-7002

Copyright © Billy Faier/Christopher Wand 2006-2023 All rights reserved

(With thanks to Gene Henriksen and David Stafford for site design)

Albums